The Religious Nature of the City

Every city is religious by nature because the human person, and thus human community, is naturally, essentially, and unavoidably religious. Such a claim should not be controversial, but because we are tempted to see political culture in a liberal frame which pretends to religious neutrality or indifference, it is a claim which I would like to present at greater length than I normally would by dwelling first on the place of religion in the ancient city. By doing so, it will become clear that the ancient, and thus pre-liberal, way of conceiving the city was ineluctably religious, and so we must never ask whether a city is secular or religious; rather, the only question we must ask is whether the religion of the city is true or false.

Examining this question prior to the advent of Christianity gives us some perspective, then. It not only helps us to see how foreign the liberal way of conceiving the city is from classical antiquity, but it help us to understand better the way St. Augustine, and the Catholic Church more generally, conceived the sacred shrines and altars of Christ as having both preserved, strengthened and elevated the sacred bonds of the Ancient City. This matters for how we understand the medieval and liberal order, and I will argue, also matters for how we should understand and oppose various pseudo-religious cultic re-settlements currently underway in our own world today, and why it is so urgent that we be tireless promoters of a public order cognizant of true religion.

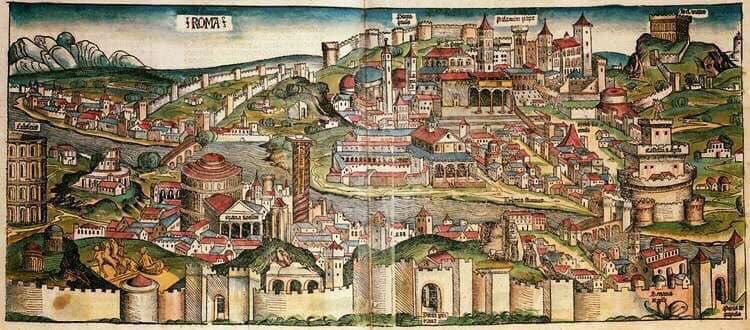

I. The Ancient City

On the hearth of every ancient Greek and Roman home was kept a small, sacred fire. It was the duty of the family to keep it lit night and day. As Fustel de Coulanges argued in his 1864 classic study, “The Ancient City,” on the religious and civil institutions of ancient Greece and Rome, this vesta or “living flame” of the domestic altar was prior to all other devotions to the gods, to such a degree that we might even say that the domestic altar was the common cradle of all natural piety — for the human soul was forged in a family, and the family was itself was a fit home for the rational, relational, and religious nature of man.

The ancients regarded this sacred fire as chaste and pure, as the wellspring of marriage, paternal authority, the happiness of family relations, as well as a fire by which wealth, property and inheritance were blessed. As the family enlarged into other families, expanding associations, and forming a city, it was this same bond of the sacred flame which united all the families, as well as all the principles, rules, laws, institutions, and mores of ancient western civilization. To extend Fustel’s metaphor, we can say that the sacred fire of the hearth should be understood as the city’s most interior altar, integral to both the good of every human person, and the good of every aspect of life together.

Fustel’s point is to show that ancient domestic religion was the constitutive core of the common good of the family, and each family had its own panoply of divinized ancestors and deities. The religion of the sacred fire “caused the family to form a single body, both in this life and the next.” (42) In this way we can understand that the ancient family was primarily a “religious rather than a natural association.” (42) This is not to say that they had no knowledge of the natural law, no knowledge that a family was natural, but that they believed the unity of a family was something more than natural. For example, ancients believed that every member of a family must be initiated into the sacred rites of domestic religion. A natural son would be disowned if he renounced this worship, whereas an adopted son would be counted a real son if he had been initiated into the sacred fire of the family. In this sense, we can see the constitutive hierarchy very clearly.

Again, this is not to say that the family was not natural. It certainly arises from human nature itself, through the union of a man and a woman producing human offspring for which they are responsible. But the natural, temporal conditions for the existence of a family were not sufficient to bind the family together as one. The family was natural, but it was also spiritually tied together by religio, by worship — the common good of the family flowed not from the gene pool but “by the rights of participation in worship.” (42) Yes, they recognized the individual person, but being a person entailed belonging to the family by way of the vesta.

In a similar way, a person also belonged to a City. In his Laws (Bk 5), Plato says that the “kinship” of the city depends on the kinship of the domestic gods. In this sense, the foundation of the city is also not “nature” as such, but worship. As these ancient cities developed, other associative bonds, such as blood, would be admitted -- but nothing was ever as foundational as religion. Even the right of property was an essentially religious idea, for every family required an immovable, stable hearth that belonged to them, that was solely their own. The heart requires soil, a stable foundation upon which to be rested, which can support the sacred fire, and most importantly, unites the family. The walls of a home are raised around religion.

Cicero would recognize the same when he wrote “What is there more holy, what is there more carefully fenced around with every description of religious respect, than the house of each individual citizen? Here is his altar, here is his hearth, here are his household gods; here all his sacred rights, all his religious ceremonies, are preserved.”

The tomb was similarly conceived as something fixed for worship, as the claiming of a space, land, property, which is intelligible for primarily religious reasons. It is thus not only possible to think of religion as the cradle of the family, but of the hearth, the home, the tomb, and yes, the city. Moderns are sometimes puzzled by ancient prohibitions against the sale of land because we fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the ancient city as fundamentally religious. The laws of the hearth were prior to the laws of the city, and those laws were theological through and through. The family was “a little society,” and the fundamental building block of the city. It had a directive principle in the paterfamilias, but it is wrong to think of the family as male-led. The father, like all members of the family, was subordinate to the spiritual power, the sacred fire, the deities of the hearth. The father had rights principally because he had duties, and his chief duty was keeper of the sacred fire along with his wife, who in Roman law was recognized as having equal dignity, if not equal rights, as mater familias precisely because she also was a keeper of the flame, the vesta. Everything about the family was thus conceived as divine to such a degree that the chief virtue of the family was “piety.” The obedience of children to their parents, and the attachment of parents to their children, were regarded as pietas — and so was the love of homeland, or patria. Ulysses longs to see not simply his “country, but “the flame of his hearth-fire,” because the love of one’s homeland is principally religious. As Catholics love the Church, so did the ancients love their homes, and their homeland as bonded together by domestic and civic religion.

Fustel de Coulanges argues that the patricians of Rome — called the gens — and their plebeian imitators, the gentes, are later developments of the domestic religion, and so the classes, that is, every gens and gentes, had religious duties to perform. The ancient city is thus not simply a “family of families,” or associative in nature, but rather the ancient city is seen as itself one, integral, whole and common good united by religion, constituted by its worship and piety at every level of familial, class and civic common life. While it was impossible to join two families into one hearth, Fustel argues that the primitive religion of the ancient city arrived at the religious idea of uniting families by another altar which could be common to them all without sacrificing anything of their devotion to the “hearth-fire.” This required raising an altar, lighting a sacred fire, to a god greater than that of any one household, a god who would bless not just one families, but many families. This is to say that the religion of the city is closely patterned on the domestic religion.

One should also consider the philosophers of a city as a kind of gens, a class bound together not by the worship of ancestors, or the heroes of the city, but by the causes and powers of physical nature which rose high above those of the hearth and the city — from the primitive Zeus to Plato’s One, there was a sacred fire of the philosopher’s speculative vision of the common good of the whole cosmos. The “religion” of the hearth, the city, and the cosmos were copies of the other at different levels, which is why they were not seen as competitors with one another despite being quite distinct.

Fustel ends his unsurpassed study with the striking conclusion: “all had come from religion.” Religion was the “absolute master” of the ancient social and political system, “both in public and private life.” (389) “The state was a religious community, the king a pontiff, the magistrate a priest, and the law a sacred formula.” (389) Where law and politics had become more independent of religion, more forgetful of its origins, Fustel argues that this was due not to a structural change but because their religion itself had lost power.

With the advent of Christ, the ancient city is forever changed. Now the common good of the family, the city, and the whole cosmos was seen through the illuminating beams of sacred light emanating from the revelation of the God-Man. This fundamentally and permanently changed western civilization. But it is important to see what it left intact, namely that the family, city, and the cosmos have their principle of unity in religion — turning only from false to true religion which has the divine power to unite us to God and one another.

The classic Christian description of this conversion of the ancient city to true religion is found throughout the works of St. Augustine.

II. The Ancient City Transfigured

Augustine himself is a good example of the transition. He grows up between two worlds, one pagan and one Christian — perfectly represented by his pagan father Patrick, and his Christian mother Monica. Because of his pagan father, it is likely that he knew from an early age the vesta of the domestic altar —he will later complain of Christians who still observe the pagan rites of the vesta.

In his own lifetime, prior to his conversion in 387, Augustine was a witness to massive civic-religious shifts, having been born only a few decades after Constantine had made Catholicism not merely a licit religio, but the privileged religion of the empire. When he was a young boy studying grammar, he may have been aware of Emperor Julian’s attempts to restore the old religion of Rome. By the time of his conversion to the Catholic Faith in Milan, under the authority of the strongly pro-Nicene Bishop Ambrose, he watched Emperior Theodosius crush many of the most prominent pagan shrines, effectively banning the old civic religion by force of law.

Yet when Augustine writes The City of God, after the gothic sack of Rome in 410, there were still many elite Romans who resented the civic-religious turn to Christianity. Roman patricians who had never accepted the Christianization of the empire from Constantine to Theodosius, suddenly started to blame the sack of Rome on Christianity. They charged that Rome was falling precisely because Christ and His Church had usurped the place of the ancestral gods. Augustine thus writes his magisterial City of God precisely to defend the Church against the desire of some to return to the pagan civic religion — as the original title reflects, De Civitate Dei Contra Paganos, The City of God Against the Pagans.

I must note in passing that one prominent interpretation of The City of God which arises in the modern period downplays the obviously civic-religious focus of the work by insisting that Augustine’s great innovation is to introduce the concept of the saeculum, which is to imagine that Augustine invents the idea of the secular city. The most important advocate of this view, Robert Markus, was a superb historian, yet despite much good and admirable work, he managed to turn Augustine into John Rawls — a view which would have been unthinkable to any medieval reader of Augustine. Suffice it to say that I think seeing Augustine as the inventor of a secular arena which is not religious at all gets Augustine exactly backwards.

The most straightforward reading of Augustine’s City, the reading which inspired more than a thousand years of interpretation, including readers like Charlemagne and other Christian rulers, was that Augustine re-envisioned the ancient city on the hinge of true and false religion, not on the liberal frame of a secular space which was neutral or agnostic about religion. Augustine does have a distinctive understanding of the secular — thoroughly united to his doctrine of divine providence —but his great contribution to the western understanding of the city is thoroughly centered on religion.

It’s embarrassing to liberal Augustinians that he spends so many books of the City of God attending to Roman religion—and they often skip over those parts. It’s an embarrassment to liberal Augustinians that Augustine thinks that religion is central to public order, law, morality, and culture. Though they show that it is possible to read him very selectively to make him safe for liberal religious neutrality, I think this interpretation doesn’t stand up even to the title of the work, let alone the structure, argument, and interpretive history.

It should be obvious that Augustine would think the human city was religious by nature because we know he thinks the human soul is religious by nature. His most famous idea of the “restless heart,” which is restless until it rests in God, is precisely the idea that we are irresistibly religious by nature — and that the way we are religious is what gives unity to our rational and relational nature as well.

So the Augustinian choice for humanity is never about choosing between being religious or not being religious. We cannot help but to be religious. There is no choice in the matter. We simply are religious. For Augustine, the only question is whether our religion will be true or false, and answering that question matters because false religion will fragment the soul and city alike just as true religion will integrate the soul and city alike.

He upholds the Greek and Roman idea that religion is what binds us together — he even traces unique etymological lineages to prove that re-ligare means something like that which makes a people adhere to one another or to God or the gods.

Yet Augustine does actually add something missing from Fustel de Coulanges account of ancient religion. He notices that just as the home and the city erect exterior altars at their center, so there is an interior altar in the heart of man, upon which we are constantly making religious offering. In his famous account of his own conversion in The Confessions, Augustine refers to exterior acts, his errors and sins, as sacrifices offered to demons on the interior altar of his heart. Augustine not only recognizes the domestic and civic altar, but he recognizes how these exterior altars shape and orient the interior altars of our very religious souls. This is not “the invention of the individual,” but rather a very Platonic way of recognizing the way the City shapes the Soul.

What binds together the soul is the same thing as that which binds together the family, the city, and the cosmos: religion, sacrifice, worship, the speculative gaze which orients all our exterior actions, and either gives the soul, the family, the city a real integrity, or it fragments, and distorts the common good. This is why Augustine argues that Rome’s fall is due to a civic-religious corruption of the Roman soul which has been mediated by the false gods of the city. Rome’s political problem is at root a religious problem.

It’s for this reason that Augustine repeatedly uses the Latin word ‘spectare.’ Anyone with a passing knowledge of Augustine knows that he’s critical of the Roman games and the stage plays of the theatre. Why? These are “spectacles” — to which we might nod our heads and say to ourselves, “yeah, the grammies are really awful.” Yet the Roman games and theatre were not only circuses which entertained and thus formed the people, but they focused the Roman gaze on the very immorality of the city’s gods, and thus deformed the soul and city alike. Roman theatre held up the immorality of the gods as either humorous or tragic, but Augustine says that the Roman soul is deformed by these spectacles not because he is against games, or the theatre, but because he is against how these spectacles shape the soul and the city alike. In this sense, he is simply consistent with the Platonic insight in the eighth book of The Republic concerning those “men who are like their regimes,” but now he emphasizes the civic-religious point: we become like what we contemplate, like what we worship and gaze upon.

Augustine personalizes the effect that Roman spectacle had upon him. “When I was a young man I used to go to sacrilegious shows and entertainments. I watched the antics of madmen; I listened to singing boys; I thoroughly enjoyed the most degrading spectacles put on in the honor of gods and goddesses — in honor of the Heavenly Virgin, and of Brecynthia, mother of all.” (2.5)

Augustine knows the Roman “gaze” from experience, and recalls the verbal and sexual obscenities performed in the theater and in the city. The goddess cults demand that men castrate themselves, sometimes with rocks, in order to serve at the altar of fertility. Priestesses perform sexually degrading rites that in a domestic context would be unacceptable, but which is acceptable because the gods demand it. He asks “who could fail to realize what kind of spirits they are who could enjoy such obscenities?” The gods of the theater and the city are not friends of our souls, and they are not friends of Rome. He asks the reader to recognize that these spectacles were created by unclean spirits who, masquerading as gods, deceive men into bad religion. The notion of spectacle, then, is critical for understanding Augustine’s civic-religious argument in The City of God.

Augustine’s point could not be clearer: the spectacles direct the Roman soul—and “the most depraved desires” of the human heart are given a “kind of divine authority.” (2.14) A bad religion had been set up within the city, and it was corrupting the Roman soul as well as the Roman city.

He cites their own “best men” on this point to ensure that they know that the critique comes not just from without but from within. Augustine cites Sallust on the moral deterioration he witnessed after the Civil Wars between the plebs and the patres, noting that after that time “the degradation of traditional morality ceased to be a gradual decline and became a torrential downhill rush. The young were so corrupted by luxury and greed that it was justly observed that a generation had arisen which could neither keep its own property or allow others to keep theirs.” (2.18)

Augustine rails against the way in which materialism and libertine hedonism in Rome are simply a human performance of the debauchery of the gods. Romans rooted their moral code only in “consent,” which becomes one great tyranny built upon Lust. He summarizes Rome’s radical libertinism thusly: “get as rich as you can, and let people do whatever they desire as long as there is consent.” (2.20) He argues that consent-based morality develops into a society curved-in on itself, and tends to punish anyone who speaks for a higher, more transcendent standard.

As if speaking for many Christians in our late liberal empire today, Augustine laments that to stand opposed to this bad-civic-religion (because of the disorder it introduces into the soul and city alike) invites only derision, cancellation, exile. He sarcastically laments that, “Anyone who disapproves of this kind of [religious] happiness should rank as a public enemy: anyone who attempts to change it or get rid of it should be hustled out of hearing by the freedom-loving majority: he should be kicked out, and removed from the land of the living.” (2.20) Once again, his point is that Rome’s problem isn’t that it’s religious, but that it’s religion fragments the soul and the city alike.

This is not to say that Augustine is hostile to pre-Christian “natural religion” as such. He thinks of Plato as the closest approximation ti Christianity possible apart from divine revelation. He praises Roman philosopher-statesmen like Cicero for directing Rome to that “complete justice” which is “the supreme essential for government.” (2.21)

Cicero sees that a republic should be bound together by a common sense of what is right — shared premises concerning the common good — and bound by the common interests, loves, and ends. But Cicero laments that instead the republic has fallen far from this standard. Cicero says in Scipio’s voice: “What remains of that ancient morality which...supported the Roman state? We see that it has passed out of use into oblivion, so that far from being cultivated, it does not even enter our minds...We retain the name of a commonwealth, but we have lost the reality long ago; and this was not through any misfortunate, but through our own misdemeanors.”

There was the “fancy picture” of the glory of Rome, and then there was the degraded reality evident to all of Rome’s greatest men. By the end of book two of The City of God, Augustine returns to the importance of the contemplative vision. He writes that Rome had not been formed by the fancy picture it had of itself, but rather it has been formed by Roman spectacle, by “acts presented before all men’s eyes for imitation, to put forward for them to gaze at.”

Augustine’s aim in the whole work was precisely to show that religion is essential to political morality, but Roman religion was simply not fit for the purpose of uniting souls, or the city, together. His deepest aim then is in proposing true religion as most proper to the civic-religious structure of Rome. Just as the Soul has an altar of the heart which can be profaned, or united to the Lord’s one true Sacrifice, so does the City need to chose which altar it will have at its center. But Augustine is crystal clear: the City will have an altar.

III. Elevating the City

America is now in a position similar to Rome after it’s “torrential downhill rush into immorality.” While we may know many Americans who have lived better than the errant theories undergirding America’s own fancy picture of itself, over time, people become what they see, the soul conforms itself to the regime, and if the regime is disordered in its civic-religious order, so will disordered souls perpetuate the disorder the regime in an vicious downward spiral.

Today we are ruled by a liberal dictatorship who demands of us a most perverse kind of worship. It is sometimes said that the progressive regime we live under is liturgical, or pseudo-religious, or some even will loosely refer to a “progressive integralism,” though its perversities can integrate nothing good, nor even allow us to partake of goods which are really common. America has “progressed” from an earlier, protestant civic-religious structure to a late-liberal religious regime that is profoundly fragmenting.

The progressive civic-religious regime is a very dangerous sort of pseudo-integralism, which is to say an inverted parody of Christianity. The good news is that this has exposed something. It has exposed the lie that a religiously neutral polity is possible at all. For all of human history, political and social order has sought religious unity precisely because religion is a precept of the natural law — we cannot do without it. The liberal dream of religious neutrality is an anomaly of a couple hundred years that is simply not natural, and so it’s simply not sustainable. So how should we live, then? There are simple things, even within our own national history, which can inspire us.

We can reclaim blue laws which are absolutely constitutional, and have a long history of legal support, structurally privileging at once God, the family, and the human need for worship and rest. As recently as 2009, the German high court reasserted the importance of upholding Sunday laws for social as well as religious reasons.

My friend Sohrab Ahmari recently argued in the Wall Street Journal that recovering blue laws can discipline the exhausting demands of capital, relieve the wearied worker, privilege the family, and make it easier for society to render what is due to God.

Along with the impulse to recover blue laws, we can recover American blasphemy laws. Those most likely to scoff at blasphemy laws, are often those most likely to enforce an alternative and unwritten set of blasphemy laws which are now more recognizable than ever before: if you offend the pieties and values of the progressive civic religion, you will be punished, canceled, censored. This is all deeply unjust not because we should not care about blasphemy, but because their religion is toxic, the gods they seek to defend are false. The Overton Window we need will entail a recovery of anti-blasphemy legislation that protects Christian speech, that discourages profanity against God’s Name. Even if such attempts were to fail in the near term, they would further clarify the true conflict that’s really before us.

We have tended to see school choice as a libertarian tool for funding students not schools. We should rethink school choice in a way which privileges schools which privilege an understanding of those pillars of western civilization: Greek Philosophy, Roman Law, and Christian Religion. That is, we should not only be trying to make toxic Critical Race Theory illegal and fight against “the gods of social justice” — a fight we’re beginning to win thanks to my courageous friend Chris Rufo — but we should legislate in ways which privilege the recovery of opening and closing every school day with a prayer that recognizes the one true God as the benevolent cause and end of all things.

We should absolutely recover regular public processions and public festivals on great Christian Feasts, and work to gain city, state, and even national recognition for special days of Christian remembrance.

But I know what you are thinking: it can’t happen.

If you think it sounds fanciful to do any of these things as a beleaguered minority in a fight we’ve already lost, you must stop to consider the reality that American life has been radically altered within a single generation on views which were once fringe. Absurd things which were thought up in dorm rooms by a tiny minority of trangressive postmodernists in the 1970s are now federal laws which determine everyday life for ordinary Americans. Things which would not have garnered ten percentage points of support in 1988 are now considered so essential for civic belief that to oppose such views is criminal. As my friend and colleague Adrian Vermeule so persuasively has reminded us, “our political world is far more fluid, far more malleable and susceptible to shaping through intentional action, especially the action of committed political minorities, than the putative realists can conceive at any given time.”

America needs a new vision — it needs a new religious vision. As I’ve argued elsewhere, with my friends Gladden Pappin and Sohrab Ahmari, we must not be afraid of political action which is predicated upon the ancient wellsprings of a classical and Christian vision for political and cultural order. We are in a vastly better speculative position that those 1970s transgressive minorities: we have a true vision of the good, and the religion that truly integrates and elevates.

The progressive altar was erected by human hands, and it can be smashed by human hands, just as Theodosius smashed the foul altars of the ancient city. But like Constantine, Theodosius, Charlemagne and Blessed Karl before us, we must also lend our hands to return the altars of our city to God.

We must recognize that our cities simply are religious. Our most fundamental political conflicts are religious and theological. Thus, Christians who care about their neighbor must not be indifferent to the sacred bonds of the city, but must oppose civic sacrilege, and work to reorient the domestic and civic altars alike to God’s heavenly city. As pilgrims with our faces set towards Christ, the bright sun of justice itself, our cause is just. We have a great hope even in this temporal order which is passing away; we have a high calling to order not only our souls, but also to order our cities rightly, on earth as it is in heaven.

Bravo! Brilliant, and very inspiring. I'm very happy to find more and more kindred thinkers and writers here on Substack, God bless you!

Great article. I never considered the fundamental nature of cities, and how whether we realize it or not they are religious in form, whether we recognize the religion or not.