The Party of Nature

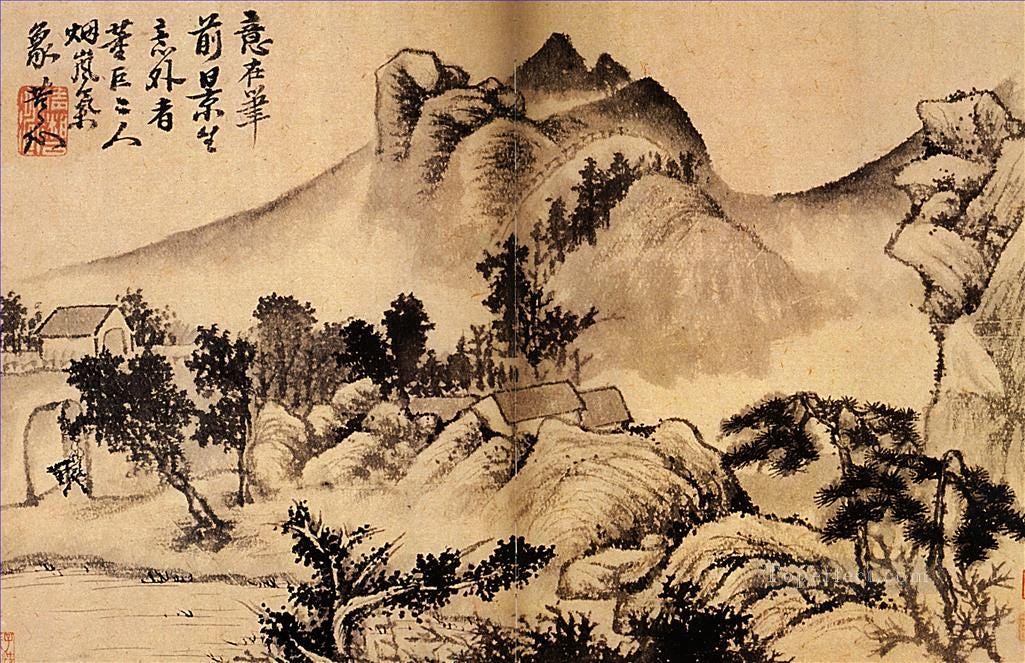

Shitao (石涛), “Village at the Foot of the Mountains,” 1699

“An authentic humanity, calling for a new synthesis, seems to dwell in the midst of our technological culture, almost unnoticed, like a mist seeping gently beneath a closed door. Will the promise last, in spite of everything, with all that is authentic rising up in stubborn resistance?”

— Pope Francis, Laudato Si

My friend and colleague here, Gladden Pappin, has a superb essay on “The Party of the State,” which argues that postliberals need not be afraid of robust governmental action oriented towards the common good. I want to suggest a corollary of this classical vision of governance: that postliberals should also be the Party of Nature. By this I mean the party that takes seriously mankind’s office and obligation of stewardship over nature, and works out that idea consistently, both at the level of political and constitutional principle and at the level of specific policies.

Today both broad political groupings, “left” and “right” and their associated political parties, take inconsistent stances towards nature. The left is commonly seen as the party of environmental regulation, and overrides libertarian claims of property rights as to land and other economic resources and their uses. Yet it excepts the human being, which it treats as a blank scroll on which the autonomous individual will can write whatever life plan it pleases. It sees the human body itself as a plastic mold to be formed through surgical modification into whatever shape or age or gender the body’s gnostic inhabitant fancies — the anthropological equivalent of corporate strip-mining that ruins the natural landscape in the name of economic utility. The left is thus radically libertarian with respect to the relationship between nature and the human person, but technocratic and statist with respect to a broad range of what are commonly seen as “environmental issues.”

The conventional right is also inconsistent, just about different things. It opposes the plastic refashioning of the human person at will, and claims to respect its nature (although its practice often belies its theory). But on other dimensions, it hardly defends the integrity of nature. Gripped by classical liberalism and dominated by corporate lobbyists, it for the most part reflexively opposes public action that protects endangered species, controls pollution and toxic substances, or mitigates the pace and effects of climate change. In those domains, it supports manipulation and distortion of nature for short-run economic benefit.

The stances of left and right, while seemingly opposed in the day-to-day struggles of conventional politics in liberal polities, share deep underlying premises. Both are ultimately derived from a dualistic view of the relationship between man and nature, one that sees man not as an indwelling steward of nature, but as an instrumental master of it. Man stands outside of nature and controls it; it is only a question where and how he wills to intervene into nature, in order to distort and transform it. Left and right disagree about where and how these instrumental interventions should occur, but both assume that it is man’s unfettered right to decide on such questions. As Carl Schmitt put it, “[e]very sphere of the contemporary epoch is governed by a radical dualism…. Its common ground is a concept of nature that has found its realization in a world transformed by technology and industry. Nature appears today as the polar antithesis of the mechanistic world of big cities, whose stone, iron, and glass structures lie on the face of the earth like colossal Cubist configurations. The antithesis of this empire of technology is nature untouched by civilization, wild and barbarian-a reservation into which ‘man with his affliction does not set foot.’ Such a dichotomy between a rationalistic-mechanistic world of human labor and a romantic-virginal state of nature is totally foreign to the Roman Catholic concept of nature.”

The Party of Nature, in contrast to both left and right, believes that plants, animals, the human body, the landscape, even the climate all have a real and objective inner integrity, unchosen by man, that man is obligated to respect, tend, and if necessary repair. The aim is neither a mechanistic exploitation of nature, nor (what is really just the mirror-image mistake) a wooden opposition to any human development of nature, but rather an integral development that harmonizes human structures, machines and lives with the landscape and its nonhuman inhabitants.

Here it is easy to assume, quite erroneously, that a non-instrumental view of nature requires Ludditism, a rejection of technology, a return to the horrors of premodern childbirth and dentistry. This is a mistake because an orientation of stewardship includes respect for man’s own nature, which is stamped with the image of God the Creator, the fabricator of nature itself. Man is properly homo faber for most of the week, and homo ludens on the Sabbath day. As homo faber it is fully human to create, to improve, to cultivate, to invent. But this orientation towards technology always bears in mind the inner integrity of the objects of stewardship. It adopts the classical conception of government, which is to say that it aims to bring the objects of its stewardship to flourishing in accordance with their real natures, rather than wrenching them into exploitable forms. It is the difference between the farmer who tends a flourishing crop and the factory farm that crams suffering animals into cages, between viticulture and agribusiness, between surgery that aims to restore the integral functioning of the body and surgery that indulges the arbitrary whims of “experiments in living.”

What does a stewardship model of governance imply concretely? What exactly does it mean for postliberals to become, consistently, the Party of Nature? The answer lies at two levels, both principle and practice.