Making Disciples of All Nations

Chad Pecknold’s Cardinal Laghi Lecture concerns the rise and fall of the heresy Pope Leo XIII called “Americanism”—and what it means for the Catholic mission to America today

Professor Chad Pecknold delivered the Pio Cardinal Laghi Chair Lecture at the Pontifical College Josephinum on March 29, 2023. We are publishing the entire lecture free to the public—please consider subscribing and become a supporter of our work here at Postliberal Order.

Dear Rector, Esteemed Professors, Seminarians, Honored Patrons, and Guests:

It’s truly a great honor to be invited to deliver your annual Cardinal Laghi Lecture. Cardinal Laghi was a friend of political conservatives, as am I. But his deepest instinct was to bring the Church’s wisdom to the nations; to seek their particular common good in a way which was cognizant of the Church’s mind about the right order of things. And so I see in Cardinal Laghi something fitting to my own work in political theology, and also for my theme tonight: To Make Disciples of All Nations.

Introduction

Making disciples of all nations is a theme I’ve puzzled over for years. Have you pondered why Our Lord does not tell the apostles to make disciples of all souls? Why not commission the apostles to work intensively for the conversion of every individual person on earth? Isn’t that how we often read the Great Commission? Christ certainly desires the conversion of every soul for whom he most certainly suffered and died, so why not just say that?

Why does Jesus take his apostles to a mountaintop in order to tell them that all power has been given to Him, and then use that power to command and commission them, as Matthew tells us, to make disciples of all nations in the Name of the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit? Luke adds that they were “sent to all the nations” and for this task, Jesus gave them power over demons, with the presumption that they will need that power in order to exorcise the nations before baptizing them. Mark and John also speak of going to the nations, to the ends of the earth, being sent in the same manner as the Father sent the Son—that is, with the fullness of power. In the second Book of Acts we get the so-called List of Nations—indeed, many different nations are explicitly named at Pentecost.

Whatever modern historical-critical scholars make of these texts, the Church’s reception of the Latin Vulgate’s Ad Gentes, “go to the nations,” has historically not been esoteric but straightforward. Christ was sent by the Father into the world for the salvation of souls, but the Church’s missionary activity is primarily done holistically, in a communal way, involving the conversion of whole peoples and nations, just as we see in the Gospels themselves. Ad Gentes concerns the Church’s mission to convert societies, political communities, and language groups. This is the witness of all the great missionary saints: ours is a communal faith, which goes down from the mountaintop, to the nations, for the salvation of many.

Think of St. Augustine who argued for the Christianization of Rome against the pagan faith which had so corrupted the people. Think of Pope St. Gregory the Great sending missionaries for the conversion of England. Think of St. Patrick converting Ireland not by going door to door, but precisely by going to the chieftains. Think of St. Boniface driving out the diabolical Norse gods by felling a tree they worshipped, and converting all of Germany with the strong support of the Royal Charles Martel. All of these missionary successes were for the salvation of souls—no question—but the Church has always sought to do this Ad Gentes, i.e. through the conversion of whole communities. Ours is not an individualistic faith, but a communal one which speaks to our social and political nature as rational and religious souls, and thus speaks to the common good of nations.

Which brings me to the problem of our mission to this country which we love: America. I love the sound of the word—a word which comes to us from the name of an Italian Catholic explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. It is a word, one might say, with a history older than our own founders. In a way, as Pope Leo XIII once said in his remembrance of Christopher Columbus, America should be ours. And yet it isn’t? Is it? Can we say why it isn’t? Do we say that our mission has been successful or can we say it has failed? If we say it has succeeded, by what measure? If we say it has failed, we must ask ourselves if our missionary strategy has some flaw within it, or if it is just due to America’s protestant history and hardened hearts, or are there now even greater obstacles to our mission, puffed up by demons, over which we think we have no power? Well, we must exclude that last possibility since Our Lord gave the Church precisely the fullness of power to remove such obstacles in order to baptize the nations.

Nevertheless, we must examine our history as missionary disciples, as ones entrusted with the power of a mission. I would like to do so tonight by revisiting Americanism. I’ll argue that Americanism is not a phantom heresy, but the very obstacle which has stood in the way of our mission. I’ll begin with Pope Leo XIII, and what Americanism meant in the broader political context of his papacy, and then we’ll turn to both the successes and failures of the Catholic mission to America in the twentieth century, where I’ll especially contrast two different strategies of mission in two mid-century theologians, John Courtney Murray and Joseph Clifford Fenton. Finally, I’ll conclude with some thoughts on how to renew our commitment to make disciples of all nations, including this one which we love, and which so badly needs cleansing and elevation.

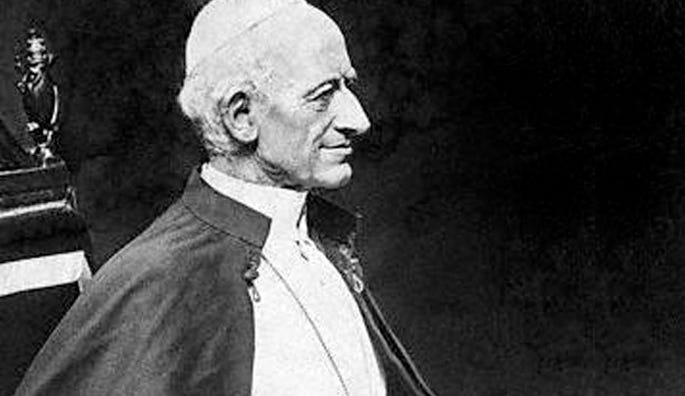

Leo’s Americanism at the end of the nineteenth century

“Americanism” was mostly a neologism of Pope Leo XIII. He invented it by way of an analogy to Febronianism in Germany, Erastianism in England, and most especially Gallicanism in France—theo-political heresies set upon “nationalizing” the Catholic Church. This was condemnable precisely because it didn’t convert those nations but effectively made the Church subject to those countries. What’s clear is that, whatever Americanism was (or is) Leo XIII tied it to a specific concern: namely, the quality of the Church’s mission to a nation.

It is often noted that Pope Leo defined Americanism in response to the writings of the American Paulist Father, Isaac Hecker, who was a passionate missionary trying to persuade his fellow Americans that Catholics were neither anti-liberal, nor anti-democratic, but were patriotic Americans whose faith was compatible with the country’s vision of itself. In my view, this characterization is unfortunate since it has, from the beginning, tempted American Catholics to think either that Leo got Hecker wrong, or that he got Hecker right but otherwise no one else, and certainly never a bishop or a cardinal, could even be credibly accused of something called Americanism. As a result, Americanism has from the beginning been dismissed, rather nervously I think, as “a phantom heresy.”

So how did Leo define this heresy, real or inagined? In 1899, he penned a letter to Cardinal Gibbons, and thus to all American bishops who were famously in the habit of regarding the American founders as having “built better than they knew.” The letter, Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae, begins with the usual good affections but Leo immediately dispenses with niceties, and turns to matters “to be avoided and corrected.” Pope Leo calls upon Cardinal Gibbons to “suppress certain contentions” which the pope believed threatened the Church’s mission in America.

While Father Hecker is named, Pope Leo does not hinge his concerns on Hecker. The basic contention he disputes is a mistaken missiological mindset which can infect a wide range of thinkers, then and now:

“The underlying principle of these new opinions is that, in order to more easily attract those who differ from her, the Church should shape her teachings more in accord with the spirit of the age and relax some of her ancient severity and make some concessions to new opinions.”

Pope Leo explicitly contrasts this mistaken missiological mindset with the Great Commission itself. He writes:

“All the principles [of both faith and morals] come from the same Author and Master, “the Only Begotten Son, Who is in the bosom of the Father.” They are adapted to all times and all nations, as is clearly seen from the words of our Lord to His apostles: “Going, therefore, teach all nations; teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you, and behold, I am with you all days, even to the end of the world.”

Leo explicitly invokes the dominical Ad Gentes command to teach all nations the fullness of the faith handed on, and not to tailor the faith to suit the spirit of the age. Hecker is an occasion and an example, but it’s very clear that Leo thinks this trend towards liberal accommodationism threatens the Church’s mission to America.

Pope Leo presumes good intentions.He knows that Cardinal Gibbons and others want nothing more than to convert the nation to the one true faith. But he warns Gibbons that this missiological strategy of accommodationism may succeed at gaining social acceptance for Catholics but it will fail to convert the nation. While the Church must seek concord with the American people, Leo stresses that any accommodation must keep the faith and morals, which were delivered once for all, intact. If the Church fails to make disciples according to the standard of the mountaintop, the Church will have ceased to have a mission to the country at all—and it’s accommodations to liberalism will have served only to change the Church, rather than to convert the nation, to the most grievous detriment of souls.

From this first point of Americanism as a kind of “inverted hierarchy” which makes the Church conform to the nation rather than work to conform the nation to the Church, Leo moves onto what he calls an even “greater danger.” What is the most dangerous mark of Americanism in Pope Leo’s view? Perhaps the answer will shock American Catholics, but shock can instruct us. Leo says the greater danger is the Catholic acceptance of what he calls new “civil freedoms” and “rights” which lessen the Church’s “supervision and watchfulness,” and instead grants the liberty of license in matters of religion, conscience, and press. He writes:

“These dangers, viz., the confounding of license with liberty, the passion for discussing and pouring contempt upon any possible subject, the assumed right to hold whatever opinions one pleases upon any subject and to set them forth in print to the world, have so wrapped minds in darkness that there is now a greater need of the Church’s teaching office than ever before, lest people become unmindful both of conscience and of duty.”

If only Pope Leo had lived to see the pornographic and propagandistic world we’ve built out of the doctrine of a free press! But it’s clear here that Americanism for Leo is synonymous with liberalism as a Pelagian doctrine—as a disordered view of freedom rooted only in the choosing power—a heretical view of liberty as license.

By way of contrast, Leo recalls Cardinal Gibbons to the mind of St. Augustine, and to the superiority of those graces which work upon the Catholic—that Christ the King is Himself at work in the Church, and so the Church must “enter the city” with this power in order to guide the nation according to a better liberty. He condemns as Americanism the tendency to view the natural virtues as sufficiently strong to carry a nation, and insists that the Church’s mission depends on the good news that nature conjoined to grace can have real unity, strength and vitality. Theologically speaking, Leo is effectively saying that Americanism is Pelagianism, and that its antidote is Augustinianism.

But the point about Americanism cannot be reduced simply to compatibilism with liberalism, or liberty as license, or Pelagianism. Leo brings his definition of Americanism back to his concern over the goal of the Church’s mission to America, and he identifies the greatest obstacle to this mission: a faulty missiological strategy which he sees emerging across many different countries:

“Finally, not to delay too long, it is stated that the way and method hitherto in use among Catholics for bringing back those who have fallen away from the Church should be left aside and another one chosen, in which matter it will suffice to note that it is not the part of prudence to neglect that which antiquity in its long experience has approved and which is also taught by apostolic authority.”

By 1899, well after the loss of the papal states, and the First Vatican Council, Liberal Catholicism was on the rise everywhere, and it cut across political differences of left and right. Liberal Catholicism had different flavors. From the Marechalian attempt to reconcile Aquinas and Kant, to France’s attempt at creating a national church without oversight from Rome, to Father Hecker’s attempts to reconcile the Church and American democracy, Leo sees a common missiological error.

The Liberal Catholic, whether on the left or right, believes he has landed upon a new method for winning the salvation of souls: show them that their principles are already Catholic, and so baptizing them requires no change at all. Whether the topic be economic or political or sexual, the Liberal Catholic employed the same missiological strategy, but Pope Leo points out that it’s not a strategy the Church in her long history has ever approved, or found to be effective. Leo concludes his letter to Cardinal Gibbons this way:

“From the foregoing it is manifest, beloved son, that we are not able to give approval to those views which, in their collective sense, are called by some ‘Americanism.’”

Americanism, in my view, was never about Father Hecker. Leo’s concern was broad, covering a vast phenomenon he saw from the privileged vantage point as universal pontiff—his concern was for the integrity and unity of the faith communicated to a nation. His concern was for the genuine conversion of America.

Twentieth Century Americanism

Catholics advanced greatly in American culture and politics throughout the twentieth century. We were deeply involved in Hollywood’s Golden Age. The U.S. bishops even established the first moral rating system for films, censoring obscenities, in concert with state obscenity laws. Catholic life was largely portrayed positively on film, despite having endured centuries of anti-Catholicism. Fulton Sheen’s “The Catholic Hour” was a major radio show with high ratings in every market from 1930 to 1950, continuing for nearly two more decades in his national television shows. In politics, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was deeply informed by Fr. John Ryan, who sought to bring the principles of Rerum Novarum to bear on the president’s expansive new vision for the nation. Indeed, in the 1930s, most Catholics would see themselves much more closely aligned to the Democratic Party’s prioritizing of the common good, uplifting the poor, with a chicken in every family’s pot; and also less aligned with the Republican Party, which Catholics tended to see as more individualistic, dedicated to the interests of the Merchant over the Family and the Worker.

In 1934, at the behest of the Knights of Columbus, Roosevelt would reward Catholic constituents by proclaiming Columbus Day to be a federal holiday in recognition of the importance of the Spanish Catholic explorer’s role in founding the nation, but in reality, he was confirming Catholics as fully American. It felt like missional “success.” Put differently, American Catholics had reasons to believe that they were, in fact, “making disciples” of the nation, and this only increased their desire to prove how deeply American they were.

Catholics had long been seen to represent, as John Locke once put it, “a foreign power,” namely the pope in Rome. This caused American Catholics, at least since Isaac Hecker, to continually fight against the stereotype that the Catholic Faith was predisposed to monarchy; and to fight valiantly for the republic. The missiological strategy required proving one’s political bona fides. Yet Catholics were always anxious to avoid the positivism and thus moral relativism implicit in majoritarian rule, so they frequently emphasized the natural law as a makeweight against democratic disorder. Since there were sufficient classical footholds for this in the American legal tradition, the makeweight often held.

But by the Second World War, American Catholics faced a new dynamic which dramatically shifted a prudential judgment into a categorical one. The new dynamic was the rise of authoritarianism—not only the authoritarianism of the neo-pagan Third Reich and the atheistic Communists, but also the authoritarianism arising from the allied Catholic Kingdom of Italy (Cardinal Laghi’s birthplace). The new dynamic would now demand that Catholics eschew or downplay the importance which Catholics naturally placed upon authority, and this would also entail downplaying authoritative Catholic teaching.

As a result, after the war, American Catholics became ever more eager to prove themselves good liberals rather than good Catholics. They became Deweyan and Rawlsian liberals, advocates for pluralism and democracy, advocates of private judgment in matters of conscience, and advocates of the very religious indifferentism that Pope Leo XIII had condemned as “Americanism.” It’s precisely this dynamic that gave us such an infamous generation of Catholic statesmen in this country.

From John F. Kennedy to Joseph Biden, the American Catholic Statesman always had to demonstrate that they were American first and that they were only Catholics secondarily, personally, but never publicly, unless, of course, it helped to prove that they were Americans first. They demonstrated the principle which they believed had to be demonstrated for the mission to succeed: namely, the spiritual power must be revealed as already ordered to the demands of the temporal power.

Within sixty years of Testem Benovolentiae Nostrae, Pope Leo XIII’s warnings ring prescient: Americanism was no phantom heresy. It was real. But this did not mean it was uncontested at the mid-century of unbridled optimism about liberalism.

The Mid-Century Contest: Joseph Clifford Fenton v. John Courtney Murray

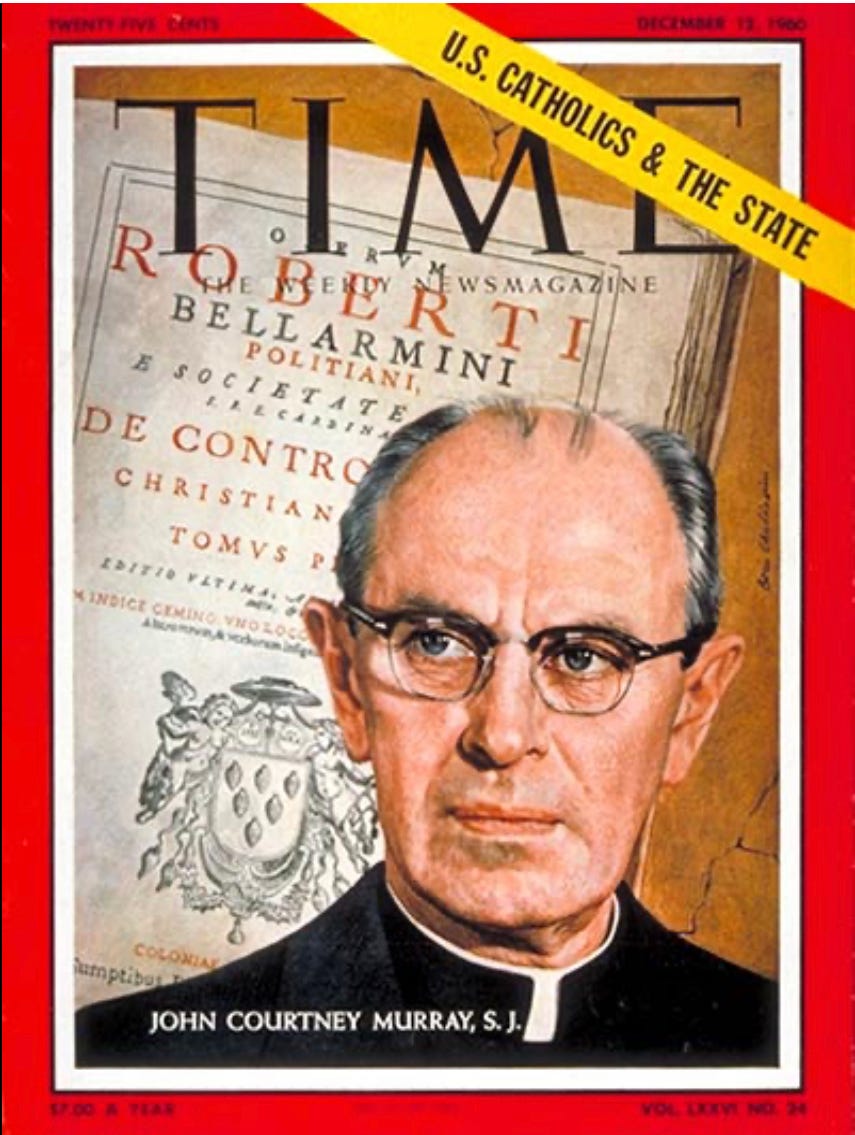

The fact that you probably know the name John Courtney Murray, and probably don’t know the name Joseph Clifford Fenton gives the game away, but it’s worth revisiting what their battle represents. The conflict between Catholic University’s Msgr. Joseph Clifford Fenton and Georgetown’s Fr. John Courtney Murray, SJ, is not well known, but it exemplifies precisely the shift that was taking place in the Catholic mission to America.

Msgr Joseph Clifford Fenton (1906–1969) was the star American pupil of the great Thomist Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP. Fenton was a cofounder of The Catholic Theological Society of America, Editor of the American Ecclesiastical Review, and professor of fundamental and dogmatic theology at The Catholic University of America. He was a giant in the public square of American Catholic letters—refuting the errors of Liberal Catholics of all stripes. He was particularly well known for advancing what is called the thesis-hypothesis distinction which regarded the liberal separation of “Church and State” as an error which could only be temporarily and prudentially tolerated.

The thesis-hypothesis distinction was itself the product of the loss of papal states, and the rise of liberal ones—it was an “emergency” distinction. Fenton railed against Americanism precisely as an inversion of this distinction which effectively collapsed the Church’s thesis that the state has an objective obligation to worship God.

Fenton nevertheless did argue that it was licit to tolerate the American hypothesis prudentially so long as Catholics recognized it as error, and worked for its correction. Fenton’s view was consistent with what Pope Leo called “ralliement” in France’s Third Republic—a call to defend one’s nation, however perverted or errant, precisely by working from within to change it. Whatever was at odds with the Catholic Faith in America was also bad for America, and so such a desire to correct founding errors was truly patriotic. As a result of Joseph Clifford Fenton’s stalwart defense of the traditional teaching on the relation of orders, Cardinal Ottaviani himself would select Fenton to be his own peritus at the Second Vatican Council—to join him in defending the traditional teaching.

On the other side of the mid-century contest was John Courtney Murray (1904–1967) who actively sought to bury this thesis-hypothesis distinction. In a heated debate in Fenton’s own American Ecclesiastical Review throughout the early 50s, Murray argued (contra Fenton) that the traditional teaching against the liberal view of religious freedom must be revised, and that the Vatican should bless the American genius for using religious pluralism as a new, durable way of relating religion and state.

In Murray’s view, the “separation” of Church and State was not just temporarily licit until better conditions could be obtained in this country, but rather the American view of state neutrality in religion was the only moral option for modern man. Murray’s fundamental claim concerned the priority of human dignity in tones redolent of the Constitution’s own enshrinement of the inviolable rights of the individual. From this fundamental claim, he reasoned that religious pluralism was a fact tied to the rights of conscience, and thus human beings had a right to religious liberty, by which he meant the state not only had no moral obligation to worship God, but but it had the opposite obligation: the state must be religiously neutral yet defend religious liberty as a natural human right.

For Murray, the American system was perfectly compatible with Catholic principles of human dignity, religious liberty, and the rights of conscience, just as the earlier tradition of concord had fit with medieval man. In some sense, he could be viewed as an historicist on the relation of temporal and spiritual power—the traditional teaching emerged out of historical conditions, and followed basic principles fit for those conditions, but a new order required a new concord. But his argument wasn’t simply historicist because he argued that the traditional view was now “morally inadequate” to the needs of modern man. We can thus begin to see how his real argument was not with Fenton, but with Rome.

Murray’s opposition to Fenton was, in fact, a cipher for his opposition to Cardinal Ottaviani, with whom Fenton was so closely associated. Murray was taking as strong a stand against the Holy Office in Rome as one could get away with, arguing that Catholic teaching on church-state relations was anachronistic, and inadequate to the moral needs of modern man. Cardinal Ottaviani received the message loud and clear.

In 1954, in his role as pro-prefect of the Holy Office, Ottaviani demanded that Murray either cease publishing on the topic of religious liberty, or submit his writing to the Holy Office for approval. Murray continued to write, and in obedience did submit his writing to Ottaviani, who denied all his requests for approval to publish. The rumor in Rome was that Pope Pius XII was intending to condemn Murray’s errors (and some of Maritain’s as well) but Pius XII died in October of 1958, succeeded by John XXIII. Murray’s silence was ended.

Murray immediately prepared and published We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition in 1960. Much of the book was constituted by either the essays he wrote against Fenton, or were the ones that Cardinal Ottaviani rejected through the 1950s. But the times had changed, as had the pope. We Hold These Truths fit hand-in-glove with the “signs of the times,” namely the social revolution which was dawning in the 1960s—and so it was celebrated as a necessary aggiornamento, a long overdue updating of how to be simultaneously fully Catholic and fully American. This would utterly transform the reception of the essays he wrote against the traditional teaching in the 1950s—and it would utterly transform how American Catholics on both the left and the right would come to see the Catholic mission to this country.

Murray quickly became a major public figure, appearing on the cover of Time magazine, advocating for a liberalization of Catholic teaching against what he regarded as the unfortunately reactionary, coercive, and authoritarian history of the Church. Murray’s liberal approach to religious liberty was in some sense politically aided by his conservative opposition to Communism. His views were championed by major institutional forces of American society, especially by Time magazine, protestant theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr, influential Republicans such as Henry Luce and John Foster Dulles, as well as Democrats like Lyndon Johnson. Fenton had been completely eclipsed, not only by the death of Pius XII, but by the American establishment’s total embrace of Murray as the quintessential American Catholic.

By 1963, the winds in Rome shifted further in Murray’s favor when he was invited to help draft the third and fourth versions of the schema on religious liberty which would become Dignitatis Humanae. But that document, which many viewed as a triumph for Murray, was prefaced with an endorsement of Fenton’s thesis-hypothesis distinction; against Murray’s wishes, the Council Fathers opened not with a rejection of the traditional teaching, but by positively upholding it as magisterially intact, and from the first paragraph:

“Religious freedom, in turn, which men demand as necessary to fulfill their duty to worship God, has to do with immunity from coercion in civil society. Therefore it leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ.” (DH 1)

This clause, upon which the whole document turns, essentially endorses religious freedom not as the religious indifferentism of the state, but as a path by which men might arrive at their duty to worship God rightly, on the path towards true religion. The Council Fathers conditionally limited the meaning of religious liberty to “immunity from coercion” in the temporal jurisdiction, but not in the spiritual jurisdiction.

What followed was nevertheless a kind of triumph for Murray’s defense of religious liberty because it did seem that, even if only in a limited or conditional sense, the Second Vatican Council had “blessed” the very Americanist view of religious liberty that had worried Pope Leo XIII just sixty years prior to the Council. Wasn’t that Murray’s goal? But the curious fact is that Murray was privately quite unhappy with Digitatis Humanae. Why?

One must understand Murray’s argument with Fenton (and Ottaviani) to see why he was personally so unhappy with a final product that appeared to favor him. To understand his unhappiness we must recall that Murray’s fundamental claim was that the traditional teaching was “morally inadequate,” which is a passive way of saying “wrong.” But the Council Fathers refused to say that, indeed, they said the traditional teaching was completely intact—upholding precisely the thesis-hypothesis distinction Murray sought to overthrow. Furthermore, they said religious liberty was justified in civil society insofar as it supported the human soul’s duty to worship God, and that truly fulfilling this duty would eventuate in the same end as the traditional teaching. One can dispute this strategy too—but Murray felt he failed to defeat the traditional teaching because, in a way, he had. The thesis-hypothesis distinction, however muted or attenuated, remained.

Yet it is Murray’s name, and not Fenton’s, that we remember because his name became synonymous with an assumed compatibility between Catholicism and the American view of religious liberty which simply obviated the need for conversion by one subtle trick of turning the hypothesis into the thesis.

Rethinking the Catholic Mission in America

In the years which followed, Catholicism in America underwent severe changes, not all of which can be blamed on “Americanism.” Nevertheless, signs of the failure of this strategy show up in every area of the Church’s life. The extraordinary liturgical experimentation which mimicked protestant worship, the dogmatic relativism which gripped Catholic intellects on the left and the right, the proportionalism in moral theology which relativized right and wrong, the dramatic rise in sexual disorder within the priesthood which corresponded to the sexual disorder in American culture, the Catholic insistence on religious liberty rather than the insistence on religious truth, and the extraordinary speed at which Catholic schools, colleges and universities became ashamed of being Catholic but proud of being Liberal—these are just a few examples of the triumph of Americanism in this country.

Perhaps the telltale sign of Americanism can be observed in the very fact that many Catholics today simply do not believe in converting America at all. They may indeed desire individual conversions, they may want to politically convert red or blue America with the veneer of Catholicism, or they may believe that America is doomed both politically and religiously, and so believe Catholics are destined for the catacombs. But whatever their differences, or rather indifferences, American Catholics seem united in their belief that converting the nation is not a “realistic” goal or mission. It is not a command we can follow, but a useless and anachronistic fantasy which doesn’t take into account the so-called fact of pluralism which Our Lord seemed to have overlooked. If they won’t admit this explicitly, they’ll just nervously change the subject to talk about how much better off we are than Germany. At this, we should at least feel some shame for the failure of the Catholic imagination. But as a friend of mine likes to say, it doesn’t have to be this way.

To strategically rethink the Catholic mission to America we would do better to understand this nation as called to something greater than the founders envisioned. America is not identical with the framers' intentions in our written Constitution, nor is it merely the aggregate of fifty states, nor is it identical with what any political party or politician imagines it to be. If we have a providentialist view of political history, we must know that America exists principally by the very will of God. It can either continue its torrential downhill slide into immorality and false religion, all the way to the bottom of the scale of metaphysical being and goodness, or it can be converted by the medicine of grace, and begin the pilgrim path of restoration in accord with the governance of heaven. We must decide which side we are on. We can’t be indifferent. Once upon a time American Catholics prayed for the conversion of Russia. But today we must work and pray for the conversion of America—with all the intelligence of St. Augustine, all the fortitude of Ss. Patrick and Boniface, all the legal and political sophistication of St. Thomas More.

We must remember that much of America was Catholic before it was either liberal or protestant. We must tell our children that one day we will see the real reason why we have so many cities named after saints like San Diego, San Francisco, St. Louis, San Antonio, and St Augustine. We have cities named after the Most Holy Sacrament—Sacramento. We have St. Patrick’s Cathedral rising up out of the center of Manhattan. We have a memory of missionaries who held just these ambitions, namely that the supernatural graces which pour from heaven onto our exterior altars would be efficacious for the conversion of the new world.

We also must remember that large parts of America were once Catholic by God’s grace and with the help of temporal power—the French and Spanish crowns. We must remember that the use of temporal power is not foreign to the Catholic mission to make disciples of all nations. Like Cardinal Laghi, Catholics must become comfortable with using temporal power for the defense of the Faith. This does not mean that the Faith is coerced—the Act of Faith is always a divine gift—but the perennial Catholic view is that the Faith can be aided, supported and encouraged, not least through rulers who have become disciples, and who dare to govern accordingly.

For Fenton and Cardinal Laghi alike, to be true friends of our country, we must dare to imagine it differently. We must reject that spirit of independence which separates the nations from those graces which can cleanse and elevate it. We must reject the religious indifferentism which claims that liberty can be found apart from true religion. We must reject the self-defeating missiological strategy of the Americanist who, whether on the Left or the Right, regards himself as a supernaturalist in private, but a pure naturalist in matters of public order. This strategy has failed. We must return to the missiological vision of the mountaintop which aims not only at the conversion of souls but the conversion of public order precisely for the same end.

Americanism traded on our good desire for that concord which comes only by way of conversion. But like all sin, it perverts our best intentions. In place of concord, Americanists (past and present) aimed at a presumption of compatibility which confused the Catholic mission to America with a counterfeit mission based on spreading the “gospel” of neutrality, indifferentism, and upholding the status quo ante of a liberalism which is passing away. Incredibly, even at this postliberal moment when it has become obvious to the world that liberalism has failed America, there are Catholics who are doubling-down on this long-held missiological error. But the good news I have to share tonight is that while the hour is late, it is not too late.

Indeed, God is merciful and patient. The Catholic Church did not convert ancient Rome when it was ascendent, but precisely when it was most dispersed and brittle. As it is for souls who must bend the knee through the trials of adversity, so it can be for nations, so it can be for us. We must now begin again. We must begin to rethink the Catholic mission in America as the Catholic mission to America. The Catholic Faith is not a private possession, to be passed on to others as their private possession. It is refuge and sanctuary for souls, and for families, and, as Our Lord very clearly taught us, it is also for the nations.

Let us not be ashamed of this mission.

Beautiful speech, Professor: cogent and concise. It took me back to my undergraduate days, particularly a class called the American Catholic Experience in which we discussed John Courtney Murray's influence on the Church and the evolution of American Catholicism.

There is so work to be done to reverse the precipitous decline of morals and virtues in today's culture that it's easy to get discouraged and deem the problem as irreversible. Lectures and discussions like this one are vital to provide hope to the dwindling faithful. Godspeed.

Thank you for this lecture, Prof Pecknold. I am not qualified to speak in substance on the subject of Catholicism. The fullest extent of my knowledge is the 6 years I was schooled in my formative years in a Catholic primary school run by the St Vincent Nuns in a foreign land. I still remember their white bonnets, ever so white and pristinely ironed. They were strict disciplinarians and great teachers. We attended mass in a Catholic Cathedral where the priest was a Jesuit from Portugal.

I just wanted to briefly say of course there is no shame in the mission of the Church, of being a Catholic and spreading the teachings of the Church. Catholics have every reason to be proud that they are Catholic. The America we see today, inebriated to the point of lost in aimless meanderings in the moral desert of indifferentism, is hostile to any moral principle or tenet that defines what is good and what is just. As you put it, hypothesis became thesis. The concern is not even about a slippery slope any more. It is about a perpendicular fall into the chasm of bottomless darkness. More than ever in America’s history since its founding does America need to re-visit the teachings of the Church, to let known the moral authority of the Church. Catholics in America do not need anyone’s permission or approval to teach a faith that embraces the values of social justice and dignity of the human person. Social justice, from my own reading, embraces Common Good. Common Good is not "good" for a select few in accordance to the whims of flavor-of-the-month “Liberalism”.