Building for a Better Liberty

Macroeconomist Philip Pilkington writes that in a postliberal age, we need to look at social engineering with a better view of human freedom.

Social engineering is not a terribly popular term these days. On the right, it is seen as something that should be associated with socialism and perhaps even communism. On the left, it is rarely discussed, likely because the old early-and-mid century progressivism in which the term was popular has given way to a more libertarian movement concerned with individual freedoms rather than improving society. The modern left’s resistance to the term makes more sense than the modern right’s. The left is simply not interested in social issues that are not ultimately individual issues. For the modern left, if anissue does not increase the capacity for an individual to “be themselves” then it is not worth trying to support this issue and so why should they think about how to build – or engineer – a better society.

The libertarian right today agrees with the left, of course. In reality, there is very little light between the two movements and ultimately, they clash over means, not ends. The libertarian left seeks to use state power to maximise individual libertarian freedom, and the libertarian right seeks to use market forces. Ultimately, both have their role in maintaining our current liberal regime. But the libertarian right is no longer a serious intellectual force. It still plays a very important structural role in the liberal regime – and that is why it still has access to enormous amounts of resources – but it is not producing serious intellectuals or interesting ideas and has not for many years. In recent years, desperate to find a point of relevance, it has started to deteriorate into crude eugenics and race hucksterism.

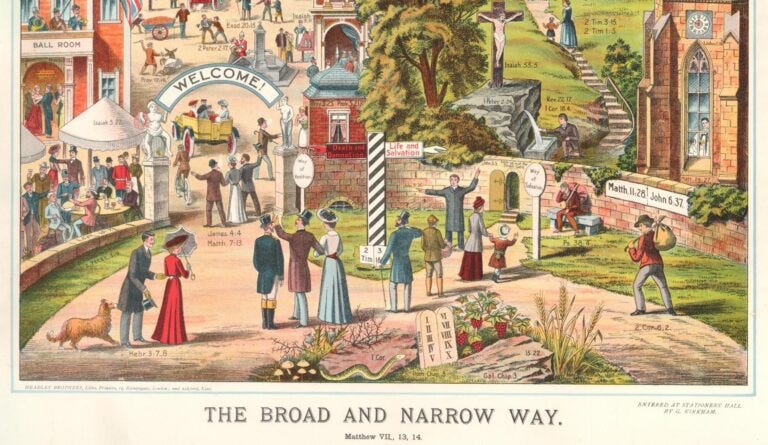

The postliberal right, on the other hand, should be interested in social engineering. If it seeks to build a better society then it will need plans to do so. Drawing up plans requires engineering. There is nothing inherently socialist about this. Indeed, the origins of the term ‘social engineering’ are not traceable to the Bolsheviks or even European social democrats, but rather to Protestants in late-19th and early-20thcentury America. It is true that the ideology of liberal Protestantism that most of these men and women subscribed to would be alien to contemporary postliberals, but it is far less alien than the libertarian missives from many contemporary libertarian Protestants.

Earp’s Social Gospel

The key work in this respect was the American sociologist Edwin L. Earp’s 1911 volume The Social Engineer. Earp emerged from the ‘Social Gospel’ movement which was, in many ways, American Protestantism’s answer to the papal encyclicals on social teaching emerging from the Catholic Church around the same time. The Social Gospel movement eventually mutated into what we would now refer to as old liberalism in America. The New Deal, for example, was heavily inspired by the Social Gospel movement and it need barely be mentioned the influence it had on the early Civil Rights movement, which was centred around the Baptist Church.

It would be a grave mistake to think that just because the Social Gospel movement eventually mutated into mid-century American liberalism, that it was always a purely liberal movement masking as a religious movement. The Social Gospel movement, at least in the early days, did see the problems in society as arising due to a fundamental conflict between good and evil. Social engineering, for someone like Earp, was primarily an attempt to reorder society to exercise what he saw as the forces of evil and which he believed were becoming more organised and developed in advanced industrial society. In this 1911 book he writes:

The powers of evil today are socially organized, and therefore the salvation of society involves social methods and machinery in order to overthrow the organized powers of evil… today it is possible to “sin by syndicate”, and therefore our methods of salvation must be socialized. [We must create] a regenerate environment so that the spiritual life of the individual may have the best chance to function and prove its quality by fruitage.

Nor is Earp shy about what the remedy is. Yes, he discusses various practical social reforms to tackle various practical problems, but ultimately, he wants to use the tools of the state to purify society in light of the teachings of the gospels. He urges his readers to pursue “a serious search for a social antitoxin that will destroy the toxic effects of social sinning in the body social; and earnest attempt to apply preventative measures of the gospel to the problem of sin as well as the redemptive agencies of the Word of God”.

Here we see that the source from which the term ‘social engineering’ arose was indeed the American Protestant answer to the encyclicals on Catholic Social Teaching. In content the two doctrines were more similar than they were different. Both were distrustful of socialism. Both emphasised something resembling the principle of subsidiarity. Both were highly focused on class conflict and on the moves by the socialist and communist left to take advantage of these tensions. There were differences too, but in many of these the Catholic Church the more liberal line such as with the question of the prohibition of alcohol. But overall there were far more similarities than there were differences.

Social Engineering in Contemporary Discourse

Yet the Social Gospel teachings were disorganized, lacking both fundamental philosophical basis and theological depth. This reflected the fact that various Protestant sects adhered to it. Methodists were as influenced by the movement as were Episcopalians andBaptists. Obviously, these groups had vastly different ideas about theology and even philosophy, to the extent that they thought about the latter. So, there was never any attempt to ground the Social Gospel movement in a firmer theological and philosophical base. Likely for this reason, there is no existing philosophy of social engineering. While it is a widely used metaphor, most of us do not really stop to think what it means.

In its initial meaning – that is, as Earp deployed it – the metaphor was direct. If you wanted to build a bridge, you would consult an engineer. The engineer would consider how best to do this given the conditions in which the bridge was to be built. Likewise, for Earp and his followers, if you wanted to build a better society you would consult a social engineer. Rather than simply standing on a street corner preaching the gospel, Earp argued, groups of social engineers could consider social problems at a macro-level and work on plans for how to address them. They could then use the churches to rally people around these problems and put pressure on the state to address them.

Today, however, social engineering seems to have a slightly different connotation. Although never clearly defined, it seems to mean something like “using technology, whether physical or social, to influence behaviour”. The likely reason why this meaning has shifted slightly is obvious: governance, whether undertaken by the state or by other corporate actors, now has much more sophisticated techniques on hand to draw on than it did in the early-20th century. Indeed, if you think about it carefully it becomes clear that social engineering is always a matter of degree. When the early social engineers set up so-called ‘settlement houses’ to help the poor improve their lives, they were ultimately focused on changing and improving peoples’ behaviour. This is perfectly analogous in a purely formal sense to the state using mass communications technology to alter peoples’ behaviour today.

When it is discussed in public, the question that social engineering appears to immediately raise is whether it is right or wrong. This touches on questions of freedom and agency. It also touches on questions of state and even Church authority and whether influencing people is ultimately an analogue to coercing people. Yet this discussion is rarely undertaken in any nuanced or sophisticated way. It seems likely that this is because of the origins of the term itself and the fact that it arose from a somewhat disorganised movement that was populated by different Protestant factions eager not to air their internal theological and philosophical disagreements over such questions of freedom and order.