Against the Politics of Envy

Professor Ed Feser on how left-wing appeals to “social justice” on questions of gender, race, and class mask a deeply antisocial ressentiment that’s destructive of peace and order.

The ideology that has in recent years come to dominate left-wing politics goes by many names: Critical Social Justice, identity politics, “wokeness,” the “successor ideology,” and so on. It also encompasses multiple sub-movements: Critical Race Theory, Queer theory, fourth-wave feminism, and the like. But a pervasive theme is that inequity as such is unjust, so that achieving equity is essential to social justice. Indeed, inequity is often treated as if it were the telltale mark of persistent and structural injustice, and eliminating it the highest imperative. And such claims are presented as if they were simply the consistent working out of principles of justice to which the modern West is already committed.

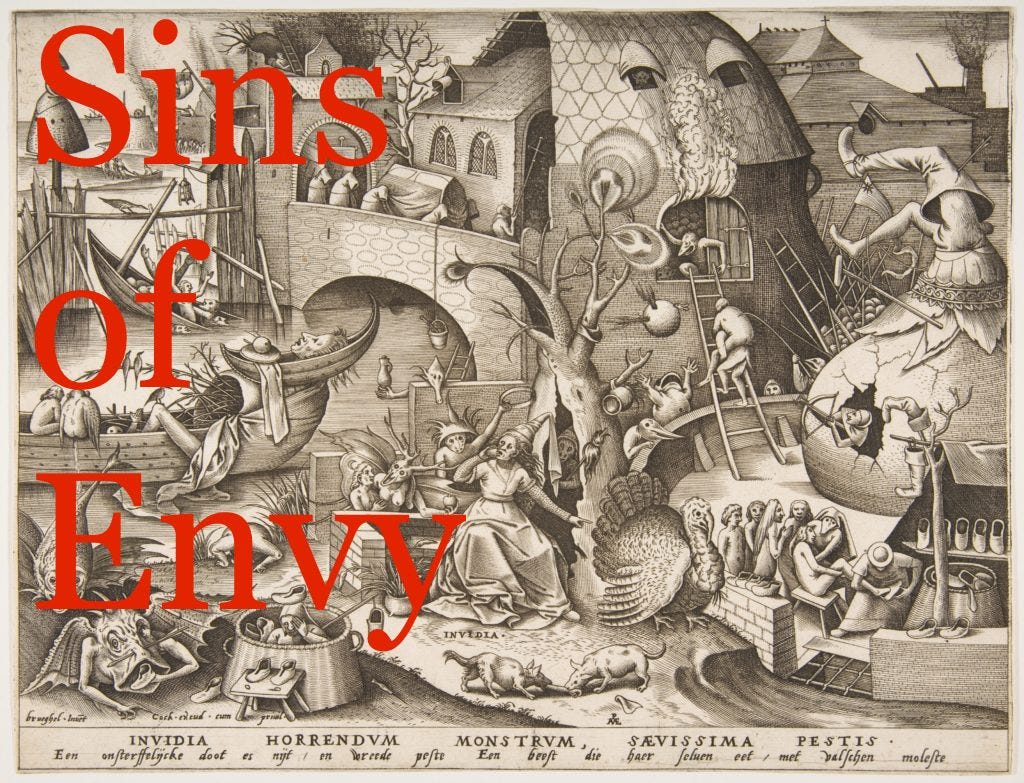

The reality is that the demand for equity has nothing at all to do with justice, but is rooted instead in one of the seven deadly sins – envy. If many modern people do not see this, that is precisely because this particular sin is itself now pervasive and deep-rooted in modern Western society. In any case, that the demand for equity flows from this sin is, or ought to be, obvious, given what moralists have traditionally said about the nature and effects of envy.