A Fidesz Earthquake Shakes Europe

Dispatch from Budapest on the morning after

In the end, it wasn’t even close.

After a campaign that saw a potpourri of opposition parties band together to topple Viktor Orbán’s popular national government, Orbán walked away from the 2022 parliamentary election with a staggering eighteen-point margin. Fidesz not only retained its two-thirds parliamentary supermajority but, in a result not predicted by any pollster, expanded its seats by two, to 135 out of 199. What Fidesz has accomplished is not only equivalent to Reagan’s eighteen-point landslide in the 1984 election—rather, it has effectively done that four times in a row.

Though the Western media already had their script written—the New York Times tucked their loss away on page A10 of the Monday edition, under the headline “Pro-Putin Leaders in Hungary and Serbia Set to Win Re-election”—Orbán’s mic drop performance left little open to question. In the run-up to the election, Western analysts portrayed the vote as on a knife-edge; Fidesz’s supposed unfair advantages would tilt the electorate narrowly in its favor, but only narrowly. Publicus Research, a Hungarian polling firm connected to a left-liberal member of the European Parliament, predicted a 47-47 tie in the popular vote. “Invasion Puts Orban in Tight Spot ahead of Poll,” wrote the Financial Times on the day before the election. A website called Balkan Insight even made the implausible claim that Orbán’s popularity in the countryside was on the wane (Fidesz won 96 percent of the vote in Hungary’s ten poorest settlements).

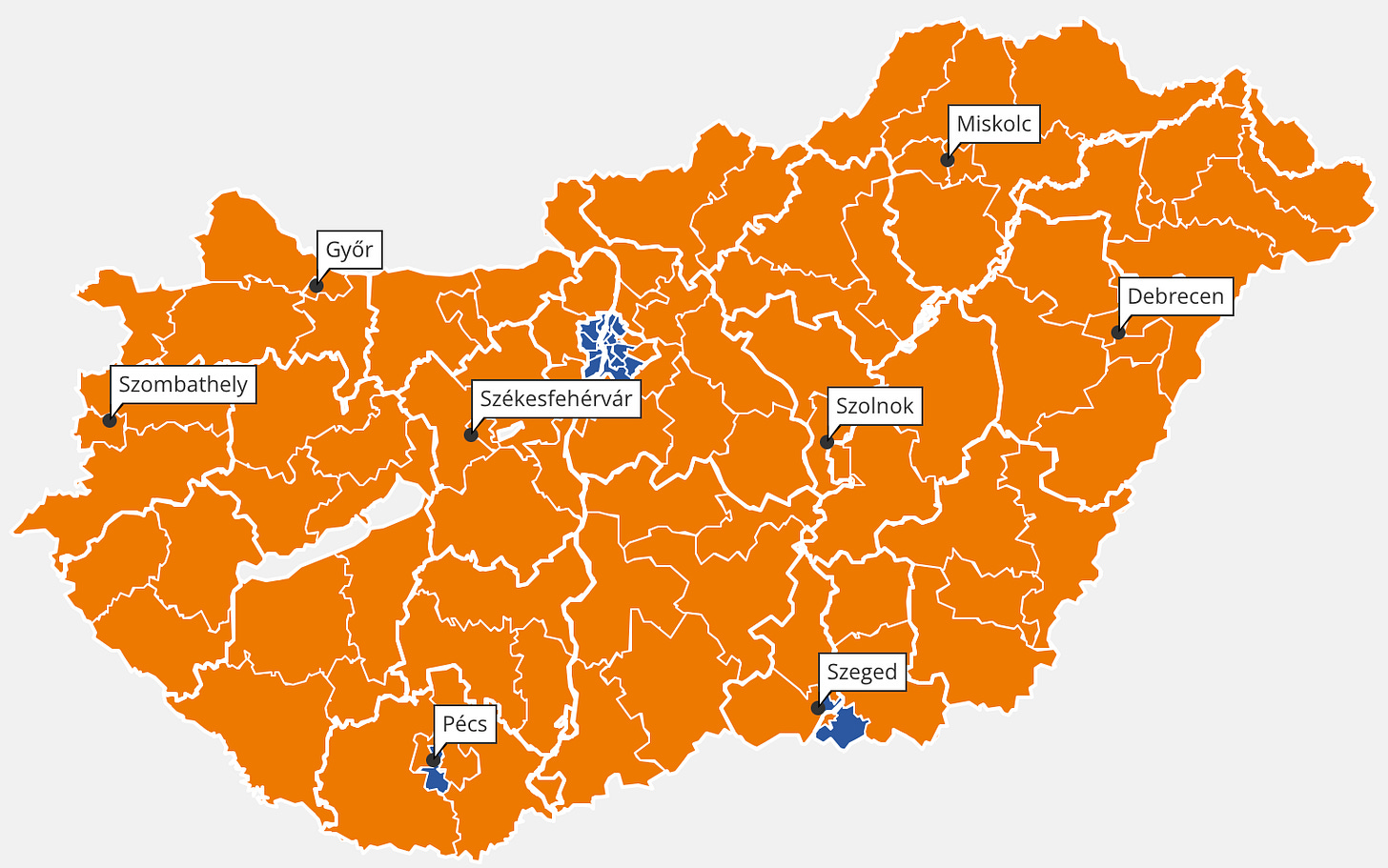

But there was no “tight spot” for Orbán—and if Western observers cannot understand why, they will continue to waste money and effort on changing the political culture of central Europe. The leader of the combined opposition, Péter Márki-Zay, closed his campaign with the slogan “Let’s bring Europe here, to Hungary.” An implausible slogan even in marginally liberal Budapest—but an insane slogan for a small-town mayor to carry into the Hungarian countryside. The results show how it was received: outside of Budapest, the entire country was bathed in the deep orange of Fidesz. The opposition’s rhetoric was designed to play well on anglophone Twitter, but the Western commentariat are not voters in this election. Orbán, by contrast, closed his campaign with the simple alternative “war or peace.”

The Monument of National Martyrs, dedicated to the victims of the 1918/19 Red Terror, just outside the Hungarian Parliament.

The scale of Orbán’s victory over the international framing of this election should not be underestimated. Each element of the liberal international regime threw everything it could at Orbán and Fidesz. International NGOs agitated for years about “democratic backsliding,” even while astroturfing opposition to Fidesz locally here in Hungary; their efforts were a complete failure. The European Union attempted to get between Orbán and his own voters by making access to billions of euros in post-pandemic recovery funds contingent upon ousting Orbán. In the middle of a war that at times has threatened to engulf NATO, members of the international community have pushed the lie that Orbán is “pro-Putin” and “anti-EU” (rather, he wants the European Union to return to its core mission of securing unity while respecting national sovereignty).

The halls of academe played their role in creating made-to-order analytic categories to describe the Hungarian system. “Ever heard of Levitsky’s concept of competitive authoritarianism?,” crowed Natalie Dodson, an assistant professor of international human rights law. Yes, if only the Hungarian people had been familiar with American political science, perhaps they would have chosen a more enlightened path.

One of the best examples of NGO-think on Hungarian electoral fraud comes from a report put out by the CEU Democracy Institute. Due to the success of Fidesz’s policies in creating a good economic environment, in 2022 the state issued a broad personal income tax refund, while also raising pay for public sector workers ranging from police officers to teachers. Not content with such generosity, NGO-think classifies public sector pay raises as a form of fraud. With a couple of examples such as this, it’s easy to see what kind of game is being played.

Will Central Europe Go the Way of Western?

Time and again in modern society, we have seen small, conservative societies steadily worn away and overturned by forces from outside. Critics of “integralist” politics like to point to the social decline of Ireland or Québec as examples of the fragility of conservative societies when washed over by the waves of liberalism. Having returned the Fidesz government to power with a fourth sequential two-thirds majority, Hungary has a chance to avoid their fate. The lesson posed by the collapse of conservative Ireland over the last thirty years is one of the dangers of rapid enrichment and deracination through an increasingly financialized economy. With the benefit of hindsight, as well as the benefit of a robust culture that has weathered other political storms, Hungary and the other central European powers have the chance to take proactive measures to forestall liberal decline.

Conservatives in the United States have sadly been forced to assume that conservative politics is purely defensive, and that the line of defense will continually recede. (Strangely, this steady failure of American conservatism goes hand in hand with its ability to amass an ever larger war chest for right-liberal think tanks.) Hungary, however, combines the political goals of the Right, the energy of the Left and the organizational acumen of a functioning administration. As Orbán begins a fourth supermajority mandate, it’s clear that Hungarian conservatism is not defensive; rather, it seeks to develop the nation positively in accord with those commitments. “We’re sending the message to Europe that this is not the past, this is the future,” the prime minister said in his victory speech. “This will be our shared European future.”

Orange indicates victory for the Fidesz-KDNP Party Alliance.

Chief among Hungary’s goals—and now known famously throughout the West—is its family policy. Here, too, Hungary does not offer the story of a steadily decreasing family policy and inevitable slide into liberalism. On the contrary, Hungary’s commitment to pro-family policies is only strengthening. It was not too long ago that Hungary spent 5 percent of GDP on its pro-family measures. This year, Hungary is set to spend fully 6.2 percent of GDP on family policy—and it began that earlier this year by fully refunding the personal income tax paid by Hungarian families in the 2021 calendar year. Meanwhile, Katalin Novák, previously minister without portfolio for family affairs, begins her term as president of Hungary in May. Combined, these measures show that family policy is not merely a policy, but rather lies at the heart of the state itself.

American conservatives who have been looking to central Europe for governmental leadership were, like most observers, expecting the Hungarian government to squeak by with a small majority. But the government’s family policies regularly receive the support of more than 70 percent of the population, across the political spectrum. Forging an active conservative policy that tangibly supports families as well as national industry—while avoiding war—is the none-too-secret formula that conservatives elsewhere can follow.

Liberalism vs. Democracy

Before the war took the central place of the campaign, the government’s child protection referendum was on track to be a focus of the campaign. A key example of proactive, pro-family measures as I suggested above, new amendments to Hungary’s Child Protection Act came into force in 2021 to provide an umbrella of care to children. As we know from life in the United States and western Europe, LGBT ideology has rapidly transformed from a movement seeking toleration and privacy to one seeking to indoctrinate children in matters of sexual identity and even “gender transition” that have no place in schools.

For a referendum to be valid, according to Hungary’s constitution, more than 50 percent of the electorate must participate and cast valid votes. Unfortunately, the left-wing opposition and foreign NGOs called on voters to spoil their ballots (e.g., by marking both “yes” and “no” to each question), thereby undermining the democratic results. We can, nevertheless, gain a fairly clear picture of what happened.

The Hungarian government posed four questions to voters in yesterday’s referendum (results):

Do you support the holding of sexual orientation sessions for minor children in public education without parental consent?

No: 63.6%. Yes: 5.2%. Spoiled: 31.1%.

Do you support the promotion of gender reassignment treatments for minors?

No: 65.5%. Yes: 2.8%. Spoiled: 31.7%.

Do you support the unrestricted introduction of sexual media content to minors, which affects their development?

No: 65.0%. Yes: 3.2%. Spoiled: 31.8%.

Do you support the display of gender-sensitive media content to minors?

No: 64.8%. Yes: 3.3%. Spoiled: 31.9%.

Because the opposition had its voters spoil their ballots, the referendum did not reach the minimum threshold for validity. Nevertheless, a clear picture emerges: two-thirds of Hungarian voters are resolutely against the promotion of sexual content, including sex-reassignment content, to children. Only a tiny fraction of voters dared to express support for these propositions. Facing another landslide defeat, the Left chose to have liberalism cancel democracy rather than allow democracy to cancel liberalism.

“Protect the Children!” referendum advertisement

International Interference

As Sohrab Ahmari observed, the Hungarian government triumphed not only over the domestic Left, but against the concerted efforts of Western powers to destabilize Orbán’s government. Aside from the countless articles in the Western press detailing the supposed unfairness of Hungary’s electoral system (actually, it gives far more seats to the opposition than the U.S. system would!), liberal politicians and media figures in the West weighed in—apparently oblivious to the fact that, outside the cloakrooms of the European Parliament, Hungarian voters do not care what they say.

Perennial “future president” Hillary Clinton wrote on Twitter that voting against Orbán provided an opportunity to “reaffirm democracy.” Meanwhile, John Cleese weighed in (incorrectly) on the historical context of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. The Brazilian soccer player Ronaldinho sent his encouragement to the opposition, and Mark Ruffalo encouraged Hungarians to vote Orbán out.

On the ground, the lack of enthusiasm for the opposition was apparent throughout the campaign. At the major national rallies around October 23 (commemorating the 1956 Revolution) and March 15 (commemorating the 1848 Revolution), Orbán drew hundreds of thousands of participants into the streets. Parallel opposition rallies were sparsely attended—a fact that narrow camera angles could hardly conceal.

While Western liberals struggled to explain an eighteen-point victory in terms of electoral unfairness, the Hungarian opposition itself was more honest. Ferenc Gyurcsány, the hated former Communist whose socialist government was defeated by Orbán in 2010 (beginning the current Fidesz rule), blamed Péter Márki-Zay himself for the defeat. At Márki-Zay’s own concession speech, he was not joined by other opposition politicians but only his family. Losing even in his home constituency of Hódmezővásárhely, Márki-Zay has now announced that he will not even take a seat in parliament.

Jobbik, the “former” neo-Nazi party that liberalized itself in order to join the combined opposition, suffered badly in the results. By contrast, Mi Hazánk (Our Homeland)—a small party formed in the wake of Jobbik’s liberalization—entered parliament with seven seats, and will likely add to Fidesz’s supermajority on certain votes.

Even in Budapest, Fidesz managed to wrangle two districts (out of Budapest’s eighteen) into right-wing hands. In the remaining districts, the opposition won consistently but generally by a smaller margin than Fidesz did in the country as a whole. The Hungarian opposition will now enter a period of deep funk. Having run on a tune designed to play well in Brussels, it is no surprise that it finds itself out of power on the banks of the Danube.

Hungary, War and the European Future

Unable to find evidence of fraud in Orbán’s victory, Western media outlets were mostly reduced to framing Orbán as “pro-Putin.” The reality, however, is that Hungary’s position has been the most openly realistic among European powers, while also reflecting the same fundamental commitments as the rest of Europe. Hungary lies in the middle of the Carpathian Basin, a natural obstacle to military movements that would otherwise occur in this central European transit zone. This combined situation of natural geographic defense (the Carpathians) and geographic exposure (as a landlocked zone between West and East) accounts for much of Hungary’s unique policy.

Hungary wasted no time in condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine immediately after it occurred. A war in the neighborhood is the last thing that Hungary wants—so to call Hungary “pro-Putin” is an absurd lie. At the same time, escalating the war through reckless rhetoric on the one hand or direct military intervention on the other poses an unacceptable risk for a country in Hungary’s situation. Orbán therefore agreed to the early calls for joint sanctions while drawing a line at freezing Europe through a stoppage on Russian gas. Although Hungary’s stance has been criticized, other European leaders often rely on it to assert what they are unwilling to. (And indeed, Polish PM Mateusz Morawiecki today notes that Germany “is the main roadblock on sanctions.”)

By the same token, as Ukraine hosts a significant Hungarian minority in its western region of Transcarpathia, Budapest and Kiev have often clashed over the language rights of ethnic Hungarians there. Budapest has thus been inclined to view the conflict as one not between democracy and authoritarianism, but rather as one between Ukrainian and Russian nationalisms—while laying the blame for the invasion squarely at Putin’s hands.

The desire of ordinary Hungarians to stay out of the conflict became markedly clear in the latter half of the election campaign. The opposition—once again playing to Brussels (in hopes of receiving EU recovery funds after its imaginary victory)—alternately cast the election as one between the West (itself) and the East (Orbán), or as the need to “choose Europe” vs. Orbán’s “choose Hungary.” For the vast majority of Hungarians, however, direct military involvement in Ukraine could only come at the cost of Hungary. As is often the case in Europe, Hungary was voicing a concern that other countries had, as well. And in the substantial results—no direct NATO intervention in the war—it is clear that Orbán and NATO are on the same page. In fact, Europe has Orbán to thank for freeing MOL, Hungary’s oil and gas producer and distributor, from Russian ownership in 2011.

As Orbán and Fidesz embark on their fourth consecutive four-year term, Hungary faces considerable economic headwinds. Thus far, Hungary’s exposure to those difficulties has been less than in other countries. Hungary has been able to control its household energy costs through national ownership and energy price caps, but an EU-wide energy crisis will affect Hungarian pocketbooks, as well. Still, Hungary’s currency sovereignty (it issues the Hungarian forint, not the euro) has led some macroeconomists to hypothesize that the forint could become more attractive given the country’s geopolitical stability.